Brutalism: Everything You Wanted to Know But Were Afraid to Ask

There has been a shift in attitude towards the architectural style of Brutalism. Buildings once dismissed as ugly have now found themselves the objects of new found affection.

The much-maligned buildings with their intimidating slabs of concrete and severe block forms have been bullied, called unkind names and threatened with demolition. Brutalist architecture is today enjoying a renaissance of sorts. People are coming out in support for some of the world’s most iconic buildings. Voices louder and prouder than ever.

When it comes to Brutalist architecture, London is home to some of the finest examples on the planet. This is a guide to Brutalist architecture in London as well as an overview of the architectural style and its origins.

What is Brutalism?

This can get complicated so here are the basics. Brutalism is a post-war architectural style defined by the use of simple block-like forms, usually made from cast concrete or brick. It is characterised by ‘Massive’ heavily-textured raw concrete (beton brut) and angular geometric shapes. Brutalism thrived between the mid-1950s and 1970s.

According to RIBA, here is what to look for in a Brutalist building:

1. Rough unfinished surfaces

2. Unusual shapes

3. Heavy-looking materials

4. Massive forms

5. Small windows in relation to the other parts

Brutalism, or ‘New Brutalism’ as it was sometimes referred to, has its roots in modernism but emerged as a movement against the architectural mainstream. It placed an emphasis on materials, textures and construction as well as functionality and equality. The brutalist architects challenged traditional notions of what a building should look like, focussing on interior spaces as much as exterior. They also showed the building’s construction, unafraid to make a feature of service towers, lifts, plumbing and ventilation ducts in their creations. In some cases, this was a celebration of the abundant energy available for the first time.

In an interview with the Financial Times, Dr Jonathan Foyle, the chief executive of the World Monuments Fund Britain, provided interesting architectural context for Brutalist buildings: “They are very muscular and everything is perhaps bigger than it needs to be, and for that reason I feel that brutalism is a modern take on gothic architecture… Both were designed from the inside out – the purpose of the building and what happens inside is the important part – the outside is merely the envelope that wraps it up.”

The short video below provides a brief introduction to New Brutalism and its origins:

History of Brutalism

Rooted in Modernism and evident in the work of Le Corbusier in the late 1940s, the term brutalism was first used in an architectural context by Swedish architect Hans Asplund in 1950 who discussed nybrutalism. In 1954 architectural critic Reyner Banham used the term more widely in his writings to refer to the work of English architects Alison and Peter Smithson. The couple who went on to create the iconic Hunstanton School in Norfolk and later, the Robin Hood Gardens in Poplar, East London. Their style rebelled against the more formal architecture of the 1930s and 40s.

The term brutalism came to refer to the functional raw concrete buildings emerging in the UK, and London in particular, in the post-war period. Due to the relatively low cost of concrete and surplus of energy, Brutalism was popular for rebuilding government buildings and providing social housing in the period of social solidarity following the Second World War.

Writer Jack Self in Fulcrum argues that Brutalism finds popularity in periods of cultural cohesion, representing “an abstract egalitarian ideal.” With individualism in architecture more likely in boom times, Self suggests that the current popularity in brutalist architecture could be related to the recession.

Brutalist Architects – the Big Players

Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier was a Swiss modernist architect. His Unite d’Habitation in Marseilles used raw concrete and is seen as an early example of Brutalism. He was a major influence on many of the architects that helped define the brutalist movement.

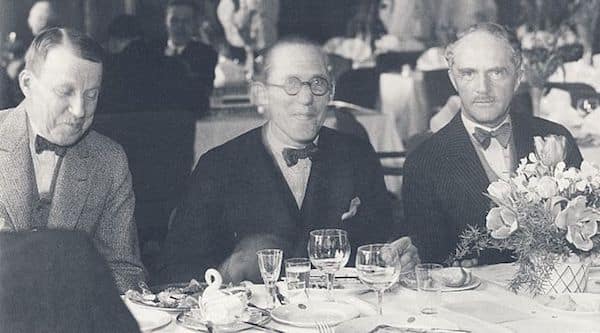

Erik Lallerstedt, Le Corbusier and Ivar Tengbom (from left) in Sweden, 1933 – public domain

Sir Basil Spence

Sir Basil Spence was a Scottish architect whose later work was categorised as Brutalist when he shifted to making social housing in the late 1950s. He is perhaps best known for Coventry Cathedral.

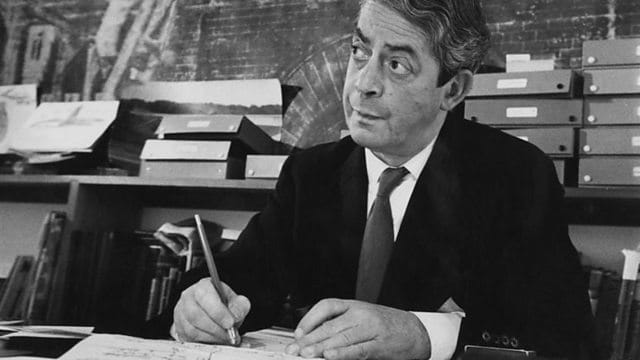

Credit: The Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Image via The Guardian

Ernö Goldfinger

Ernö Goldfinger was born in Budapest, studied in Paris and went on to create some of London’s most famous and controversial Brutalist buildings. Famously Goldfinger lived at his Brutalist Balfron Tower in East London for a couple of months in 1968. He invited residents for champagne so that they could feedback on what it was like to live there.

Erno Goldfinger at 2 Willow Road via www.ft.com

Sir Denys Lasdun

Sir Denys Lasdun was an English architect behind many of London’s most iconic brutalist buildings including the Royal National Theatre on Southbank and 20 Bedford Way in Bloomsbury. He used rough textures in his concrete forms, in particular wood ‘shuttering’ produced when the concrete was cast in situ.

You can hear the man discuss his buildings and some of the music he loved via the BBC’s Desert Island Discs or for more information on his career view our interactive timeline of Lasdun’s life.

Our blog on the Story of 20 Bedford Way is the perfect place to learn more about the venue and Lasdun’s work on it.

Image credit: BBC

Peter and Alison Smithson

Alison and Peter Smithson were a highly influential husband and wife architectural partnership that pioneered New Brutalism. They were behind the controversial Hunstanton Secondary Modern School in Norfolk, which was completed in 1954 when the couple were still in their twenties.

Image via blog.mid2mod.com

Brutalist Architecture London

15 Examples of Brutalism in London:

Trellick Tower, Kensal Town

Ernö Goldfinger

1972

Balfron Tower, Bromley-by-Bow

Ernö Goldfinger

1966

By Sebastian F (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons

One Kemble Street, Holborn

Richard Seifert/George Marsh

1966

Credit: David Baugh

20 Bedford Way, Bloomsbury

Sir Denys Lasdun

1977

National Theatre, South Bank

Sir Denys Lasdun

1976

Hayward Gallery, South Bank

Hubert Bennett/Jack Whittle

1968

Queen Elizabeth Hall, South Bank

Higgs and Hill

1967

Image via Wikimedia commons

Robin Hood Gardens, Poplar

Peter and Alison Smithson

1972

Sadly, the demolition of Robin Hood Gardens began in 2017.

Weston Rise Estate

Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis

1963-69

The Barbican Estate

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

1969

Crescent House, Golden Lane Estate

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

1959

Image via thelondonphile.com

Ministry of Justice/102 Petty France

Sir Basil Spence

1976

Photograph: Andrew Dunn, 2004 – CC by SA 2.0

Pimlico School, Pimlico

John Bancroft

1966-1970

Hyde Park Barracks

Sir Basil Spence

1970

By Karl1587 (Own work) Public domain

Where to Find Brutalism on the Web

Tumblr

Fxck Yeah Brutalism – Michael Abrahamson collection of brutalist images from across the globe

Architecture of Doom – Photographer Weronika Dudka shares stunning images with handy alphabetical indexing.

Procrete – Black and white images of brutalist architecture from across the world. Also features some great construction shots.

Toby Bricheno – musician and author of the Londonist article on Brutalist London

Brutal House – Brutalist books, posters and more from Peter Chadwick.

Simon Phipps – photographer and Brutalist enthusiast

New Brutalism – Simon Phipps’ fantastic account.

The Brutal Artist – architectural artwork

Check out our guide to the 13 best Brutalist Instagram accounts for more visual inspiration.

The Brutalism Appreciation Society on Facebook

Blogs/ Brutalist Websites

Further Reading and Resources on Brutalism

David Adjaye introducing two Brutalist buildings in a BBC video https://youtu.be/h_xF7xqgWqw

Toby Bricheno – fantastic article on London’s Top Brutalist Buildings https://londonist.com/2012/05/londons-top-brutalist-buildings.php

Barnabas Calder – Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism – published by William Heinemann

John Grindrod – Concretopia: A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain

Dave Hill – https://www.theguardian.com/uk/davehillblog/2011/jun/22/london-new-brutalism-film-appreciation

John Meades – A-Z of Brutalism in the Guardian. Also, his BBC series Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry is well worth a watch.

Anthony Paletta – Brutalism in The Awl – https://www.theawl.com/2014/06/brutalisms-bullies

Blue Crow Media – Brutalist London Map – you can now purchase a well-designed map exploring some of London’s brutalist buildings.

Tom Spooner on Brutalism & Music – An exploration of the relationship between brutalist architecture and music.

If you would like to host an event at Sir Denys Lasdun’s iconic 20 Bedford Way please contact us today.